The articles on this page originally appeared in JSSUS newsletter Volume 48, no.4, 2016.

Real-Life kantei-of swords , part 10: A real challenge : kantei Wakimono Swords by W.B. Tanner and F.A.B. Coutinho - Page 34

Volume 48, no.4, 2016

Real-Life kantei-of swords , part 10: A real challenge : kantei Wakimono Swords

W.B. Tanner and F.A.B. Coutinho

Introduction

Kokan Nakayama in his book “The Connoisseurs Book of Japanese Swords” describes wakimono swords (also called Majiwarimono ) as "swords made by schools that do not belong to the gokaden, as well other that mixed two or three gokaden". His book lists a large number of schools as wakimono, some of these schools more famous than others.

Wakimono schools, such as Mihara, Enju, Uda and Fujishima are well known and appear in specialized publications that provide the reader the opportunity to learn about their smiths and the characteristics of their swords. However, others are rarely seen and may be underrated. In this article we will focus on one of the rarely seen and often maligned school from the province of Awa on the Island of Shikoku. The Kaifu School is often associated with Pirates, unique koshirae, kitchen knives and rustic swords. All of these associations are true, but they do not do justice to the school.

Kaifu (sometimes said Kaibu) is a relatively new school in the realm of Nihonto. Kaifu smiths started appearing in records during the Oei era (1394). Many with names beginning with UJI or YASU such as Ujiyoshi, Ujiyasu, Ujihisa, Yasuyoshi, Yasuyoshi and Yasuuji , etc, are recorded. However, there is record of the school as far back as Korayku era (1379), where the schools legendary founder Taro Ujiyoshi is said to have worked in Kaifu. There is also a theory that the school was founded around the Oei era as two branches, one following a smith named Fuji from the Kyushu area and other following a smith named Yasuyoshi from the Kyoto area (who is also said to be the son of Taro Ujiyoshi). Little is formally written about the school, but in the AFU Quarterly from 1995, an article from the Token Shunju by Okada Ichiro in August 1994 was translated and published. This is the most comprehensive article we have seen on the school. Okada gives his reason for writing the article as, “the sword books commonly available seem to look with disfavor on swords made in Awa no Kuni, which is now Tokushima-ken on the island of Shikoku, and provide very little information about the smiths from there. It is for this reason that I have selected this article.” Normally all you find are references and anecdotal stories involving Kaifu swords, so thankfully Okada has provided a little more material.

When studying swords from the Kaifu School one must break them down into three subgroups; those made in the Koto era, early Shinto works and “everything else”. The

“everything else” category is what most people encounter when they think of Kaifu. These include the often seen “kitchen knives” or swords made in the kata kiriba zukuri style, (they have a bevel on only one side like in a kogatana), various long hira zukuri wakizashi sometimes referred to as pirate swords, (Shikoku Island did a good business supplying Japanese pirates) and many Shinshinto swords made in the late Edo era.

When attributing a sword to Kaifu, the NBTHK normally assigns a Shinto or Shinshinto designation to the attribution to help distinguish the category. What is rarely seen are Koto works, particularly signed ones. We will explore some theories on why we think this is so.

The Awa province on the island of Shikoku and particularly the Kaifu district is on the cross roads of several powerful Daimyos. To the south are Kyushu (Saikaido) Daimyo fiefdoms and to the north are the Honshu (Sanyodo) Daimyo fiefdoms. As Okada stated, the Lord of Kaifu needed a strong army to defend his territory and brought in sword expertise from the north and the south to develop what became known as the “Kaifu-To that were excellent in keenness and rich in individuality”. What this means for those of us studying Kaifu swords is that they possess a variety of styles and characteristics and in some cases could be considered experimental! Among the finer pieces it is not uncommon to see swords that look Yamato, others that could be mistaken for Soshu and some that could be considered Soden Bizen. As we enter into the Shinto era, many take on Sue-Bizen characteristics. In a NTHK REI Magazine article from 1992 it is mentioned that the smith Hikobei Sukesada migrated from Bizen to Awa and brought with him the Bizen tradition. We have also seen it stated several times that good Kaifu works can be mistaken for works by GO (Yoshihiro), or better Soshu works.

This leads us to the question of why do we see so few Koto Kaifu swords? In reviewing the NBTHK Juyo results, we found only one Kaifu sword. This sword is signed Yasuyoshi and partially dated. A review of this sword will be done later in the article.

An internet search (Japanese and English) found several Shinshinto and kata kiriba zukuri style Kaifu swords for sale or sold, but only a handful of Koto Kaifu for sale or sold. Signed Koto swords are even rarer. The oshigata books also have very few examples from this school. Why is this so? Obviously there were many swords produced to support the Kaifu army, where are they? We believe that many of the early Kaifu swords were mumei or had their signatures removed. Since Kaifu swords didn´t possess a specific characteristic but borrowed from many traditions, it is likely that many are attributed to other schools or traditions. Perhaps, many had gimei signatures put on them for other traditions or schools as well?

The sword to be reviewed

We will now examine a sword that we believe is a typical challenge for kantei of Kaifu swords. The sword has been to Japan Shinsa twice with differing results and also had kantei done by a visiting expert from Japan who in about thirty seconds said; “Oh, this is a Kaifu sword from the mid to late 1400’s”, but also said that other experts would classify it differently.

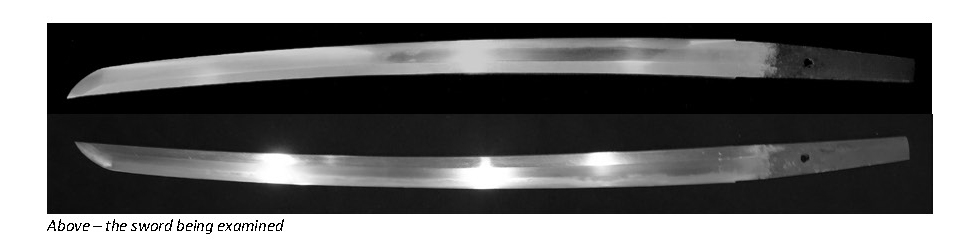

The sword being examined is a shinogi zukuri wakizashi of the following description:

Details

Nagasa

Sori

Motohaba

Sakihaba

Kasane

Kitae/Boshi

Hamon

Utsuri

Ubu or o- suriage with Kiri end

Ihori mune

Katte sagari yasurime

50 cm

1.5 cm

Saki sori

2.9 cm

2.0 cm

7 mm

Darkish tight ko-itame with chikei

Ichimai with long kaeri , pointed ko- maru, hakikake

Notare based complex nie deki gunome midare with deep nioiguchi and ashi, sunagashi, kinsuji, nie and ara-nie in the hada. Tobiyaki and muniyaki

none

When viewing the sword in hand what is most noticeable is the dark, tight and fine jigane and the nie scattered in the boshi and along the habuchi as well as the dark ara- nie scattered in the hada.

As a result of submitting the sword for shinsa in Japan the sword was given one attribution to Kaifu (assume Koto, since no reference to Shinto or Shinshinto was given) and the other to Bizen Gorozaemon Kiyomitsu (Eiroku - 1558). The purpose of this article is to understand why there were two attributions and to try and identify the Kaifu maker of this sword, since we believe this is a Kaifu sword. (Two of the three attributions say so)

However, this sword presents several challenges. First the sword is mumei or had its signature expertly removed. Second the sword was not properly polished. In order to view many of the fine details of the jihada a thorough cleaning and the use of

magnifying equipment and photography was required to observe some of the characteristics of the sword.

Examples of Kaifu swords.

In the above mentioned article from AFU there were three examples of Kaifu Swords, all signed, respectively Yasuyoshi, Yasuyoshi and Yasuuji. The first of the three signed swords is the only Juyo on record we found for the Kaifu School and by coincidence fits the description of the sword we are examining. We also have two other mumei examples from the market attributed to Yasuyoshi, which fit the description of the sword we are examining as well.

In addition, we will present several other Koto examples from the market that do not fit the description of our sword, but demonstrate the wide variety of characteristics found in Kaifu Swords.

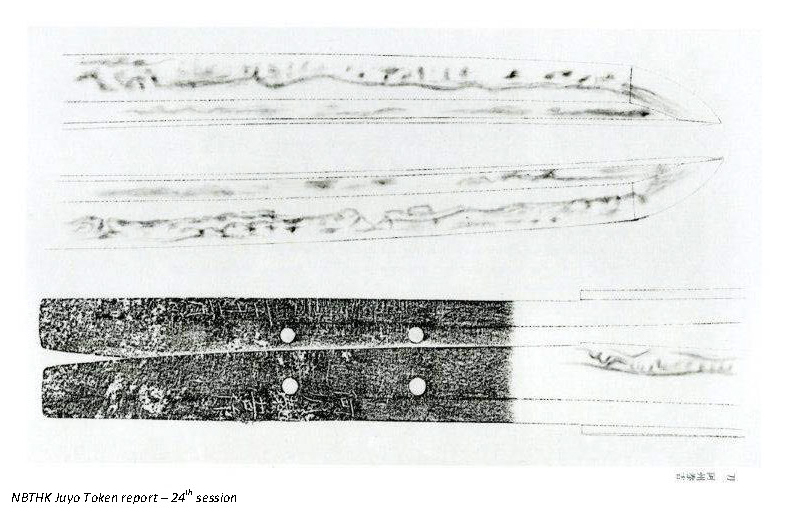

Example 1 –

This is an ubu shinogi zukuri katana signed “Ashu Yasuyoshi saku” on the omote side and “ XX ni nen nigatsu hi” on the ura side. It has a 68 cm nagasa with 1.6 cm of sakisori. The motohaba is 3.0 cm, The sakihaba is 2.0 cm and the nakago nagasa, which is slightly suriage, is 20.2 cm and has a negligible sori. The sword is constructed with tight ko-itame with chikei and scattered nie. It is mitsumune and the nagako is kiri with katte sagari. The jihada is the interesting part. It is a complex combination of notare and nie deki based gunome midare with frequent ashi, yo and sunagashi. There is tobiyaki and muneyaki. The boshi is ichimai with a long kaeri and hakikake.

37

th session

th sessionThe sword received the designation as Juyo Token in the 24th Juyo selection and is described by the NBTHK as follows:

“The works of Ashu Kaifu School are generally referred to as mountain swords of Kaifu. Their swords are, like many of those of the wakizashi kata kiriba zukuri style, not very sophisticated. This sword bears a signature (inscription) of five letters, meaning "made by Yasuyoshi of Ashuu". The year inscribed on the back side is not legible. This sword smith has other works dated Daiei 5. So this sword was probably made around that time. There is a tale in which Kaifu's sword turned into KOU 江. There could also be a tale or tales related to the sword 地刃 Jiha and to the boshi 帽子 of these swords.”

This is a very unusual Juyo sword description. Normally the NBTHK praises the sword and the smith, which is why it received the Juyo designation. This description has a negative tone prescribed to the Kaifu School and this sword. It also describes the “kitchen knife” and kata kiriba zukuri style swords of later Kaifu, which this sword bears no resemblance to. The Juyo designation appears to have been begrudgingly given to a sword from Kaifu!

Example 2 -

This is a sword which appeared on the market several years ago and was attributed to Kaifu Yasuyoshi by the NBTHK in 2004. This is an o-suriage shinogi zukuri mumei katana. It has a 62 cm nagasa with sakisori. The sword is constructed with ko-itame

and mokume with chikei and scattered nie. It is ihori mune and the nagako is kiri with katte sagari. The jihada is a complex combination of notare and nie deki based gunome midare with frequent ashi, yo and sunagashi. The boshi is almost ichimai with a long kaeri becoming muneyaki and hakikake.

Although the sword does not have as much muneyaki or any tobiyaki as the Juyo

sword does, the characteristics of Yoshiyasu are present.

There was also a sword sold by Nihonto.us (#S0232) which the NBTHK attributed to Yasuyoshi. It is a mumei 62 cm katana with a motohaba of 2.9 cm, sakihaba of 2.0 cm, a kasane of 6.5 mm and with “pronouced sakisori”. The website describes it as follows; “the hamon is very complex hirosuguha with ashi, yo, choji, ko-choji, hako gunome, kinsuji, inazuma, ha nie, tobiyaki, hataraki, muniyaki and areas of sudareba, nado. The jigane is itame nagare with ji nie and chikei..” The characteristics and construction of this sword is a close match to the wakizashi being reviewed.

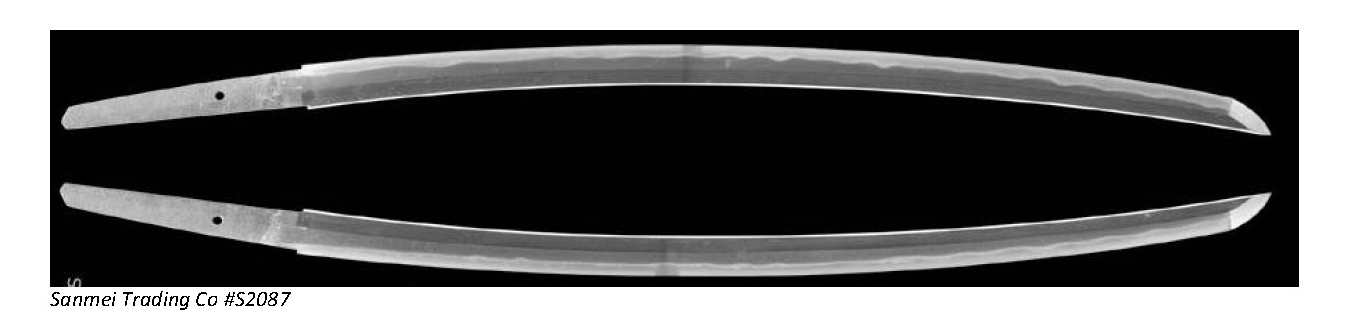

Example 3 –

This is a sword from Sanmei Trading Company of Japan that is attributed only to Kaifu, but differs from the other two in jigane, jihada and nakago. It is an ihori mune, shinogi zukuri mumei katana. It has a 64 cm nagasa with 2.4 cm of sakisori. The nagako is ubu in a iriyama shape with osujikai filemarks. The jigane stands out in a mixture of itame, large mokume and some ayasuji with chikei. The hamon is a regular notare with ko-gunome and a bright habuchi of ko-nie. There are many ashi and sunagashi as in the other swords and the boshi is nearly ichimai with hakikake, but

lacking a long kaeri or muneyaki. Overall it is a much more restrained jihada, less

Soshu than the other two.

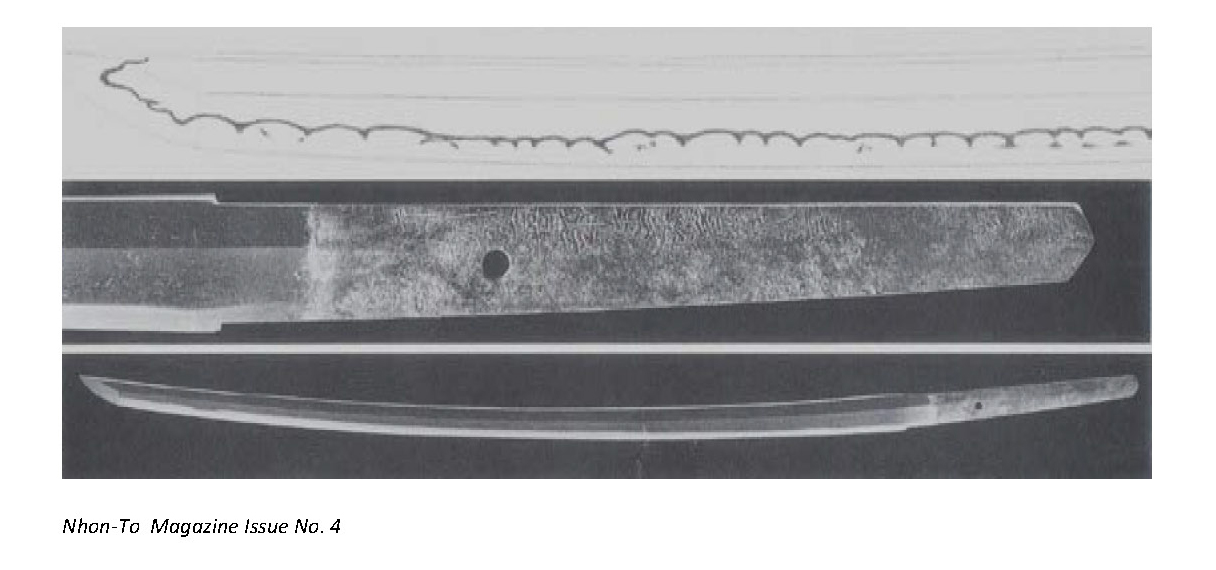

Example 4 –

In the The To-Ken Society of Great Britain Nihon-To Magazine issued in June 1996 is an example of a late Muromachi Kaifu katana that looks similar in workmanship to a Sue- Bizen sword. The sword is an ihori mune, shinogi zukuri katana signed Ashu Kaifu ju Fujiwara Ujiyoshi. It has a 61 cm nagasa with 1.82cm of sakisori. The motohaba is 2.91 cm, the sakihaba 1.94 cm and it has a kasane of 7 mm. The nagako is ubu in iriyama shape with katte agari filemarks. The jigane is a tight mixture of itame and mokume with ji-nie. The hamon is ko-nie based suguha with choji and gunome ashi and yo. The boshi is based on o-maru midare with a point and short kaeri. This sword appears to have borrowed heavily from the Sue-Bizen tradition and could be mistaken for a sword from that school.

Example 5 –

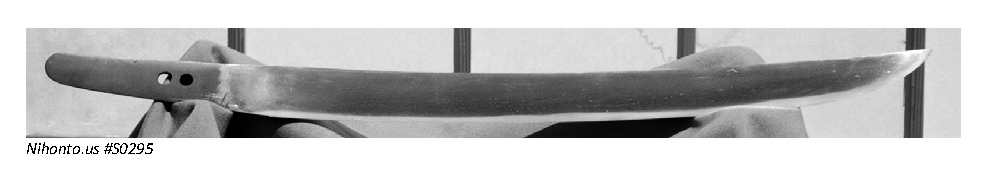

This wakizashi was offered by Nihonto.us and is shown only as an example of the immense variety of workmanship and characteristics found in Kaifu swords. This example is a late Muromachi mumei wakizashi attributed by the NBTHK to Ujiyoshi but made in the Yamato tradition. The sword is an ihori mune, hira zukuri mumei

wakizashi. It has a 43 cm nagasa and shallow sakisori. The motohaba is 3.28 cm with a kasane of 7 mm. The nagako is ubu in a kurijiri shape. The jigane is mostly masame with prominent silver streaks throughout. (very unusual) The hamon is suguha based ko-midare with sunagashi and ara-nie in the hada. The boshi is ko-maru and a very short kaeri. The scattered ara-nie is characteristic of many Kaifu swords.

The other attribution??

As we stated before, the sword being examined also received an attribution to Bizen

Gorozaemon ju Kiyomitsu from the Eiroku era (1558). So how is this possible?

Let´s consider a couple of facts. First the sword is in poor polish, therefore characteristics, such as utsuri may not be visible. Second, the Kaifu School received influence from many different traditions, including Sue-Bizen with the arrival of Hikobei Sukesada. Considering these facts, let´s review the characteristics of Bizen Gorozaemon ju Kiyomitsu’s work. In Markus Sesko´s eIndex they are recorded as follows:

“compact sugata with a chū-kissaki, somewhat standing-out itame mixed with mokume or also a fine and densely forged ko-itame with ji-nie, the hamon is a hiro-suguha or chū-suguha with peculiar ko- ashi with a compact nioiguchi, his peculiar ashi are also called „Kiyomitsu no ushi no yodare“

(清光の牛のよだれ, lit. „Kiyomitsu´s ox-saliva“)” (Markus Sesko eIndex)

Gorozaemon ju Kiyomitsu was also known to temper swords in variety of styles such as o-notare, hitatsura and gunome-midare, all with very active hamon. In the NBTHK Token Bijutsu # 427 & 467 there is an example of a Katana that is forged in tight ko- itame with chikei. It is tempered in gunome-midare and ko-choji with much ashi, sunagashi, yo, tobiyaki and hakikake in the boshi. Nie is scattered throughout the hada. With the exception of the ichimai boshi and muneyaki it is similar to our subject sword and most of these characteristics can be seen in the sword we are examining.

What is not consistent is the lack of utsuri in our subject sword as well as other Kaifu

swords. This would generally preclude an attribution to a Bizen smith.

However, it is interesting to note that the third (and last) generation of Kaifu Yasuyoshi also worked during the same time period as Gorozaemon ju Kiyomitsu. (Eiroku – 1558).

Conclusion

Based on the description of the Juyo and other Yasuyoshi swords described above we believe an attribution to an early generation of Yasuyoshi is reasonable. We also believe that if the sword were properly polished and resubmitted for shinsa, that this attribution would be upheld and possibly upgraded to a tokubetsu hozon certificate. Koto Kaifu swords are very rare and those in good condition are worthy of respect.

Although the School is not well known and even derided, the fact that it produces interesting and well-made examples of wakimono with mixed traditions can provide us with hours of enjoyable (often frustrating) research and study. It is for this purpose, as Westerners, we love and study Nihonto.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Fred Weisberg for kindly providing us with a copy of the Juyo Document and to Prof. Yukihisa Nogami for translating the strange comments of the Juyo certificate. Prof. Nogami told us that the KOU in the document apparently means that the sword transformed itself in a big river.

References:

Nagayama Kokan (1997) - The Connoisseurs Book of Japanese Swords, Kodansha International, Tokyo

Honma Junji, NBTHK Token Bijutsu No 596 & 609, Tokyo, Japan

Nakahara Nobuo (2010) - Facts and Fundamentals of Japanese Swords: A Collector's Guide, Kodansha International, Tokyo

arry Afu Watson, AFU quarterly, No. 1, page 23-33, January 1995, New Mexico, USA.

ihonto.us Website, Sword Numbers S0295 and S0232, www.nihonto.us

anmei Trading Company, Japan, www.sanmei.com, item number S2087

arkus Sesko, eIndex of Swordsmiths, eBook version

NBTHK Token Bijutsu Kantei No 427 & 467, Tokyo, Japan